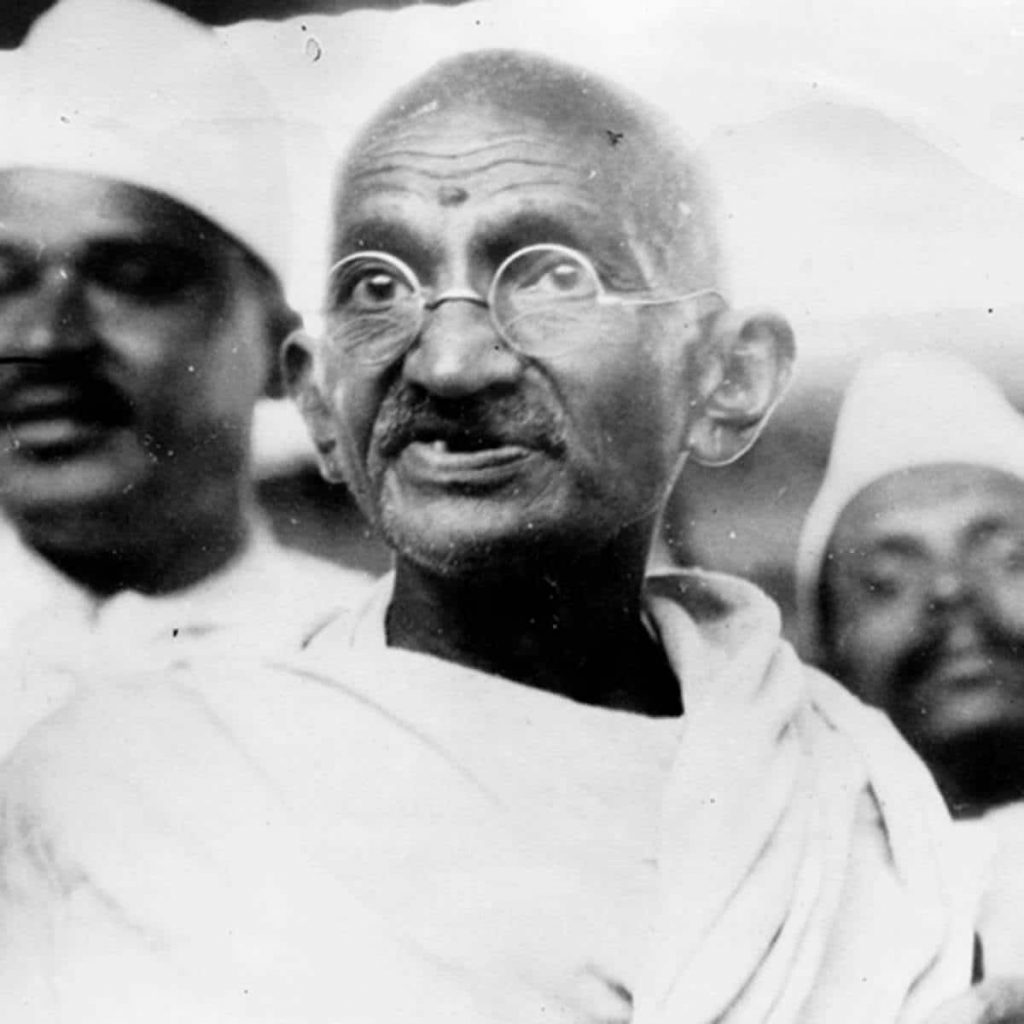

His name was Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. His followers called him “Mahatma”, which in Sanskrit means “Great Soul”.

At the age of 19 he left home to study law in London. Upon returning to India he set up a law practice in Bombay with not much success. Consequently, Gandhi became an Indian immigrant in South Africa where he was subjected to discrimination and even beating by white members of the community. After 20 years in South Africa he returned to India in 1915 and we can envision him in an ashram (modest religious retreat) near Ahmedabad praying and meditating

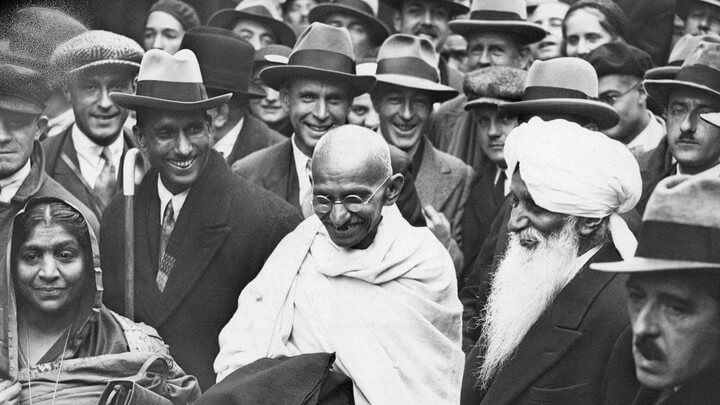

Here our story of a great leader and “Salt march” commences only to reach its public peak in 1930 when Time Magazine named Gandhi “Man of the Year”. In this ashram Gandhi planned superb leadership action that would shake the foundations of Britain’s colonial Empire and eventually lead to the independence of India. The Satyagraha, or civil disobedience as we know it, entered the political jargon and has demonstrated the superiority of leadership based on a referent power source over leadership based on a coercive power source in 84 the so called “Salt March”.

Britain’s Salt Act of 1882 prohibited Indians from selling salt or collecting even small lumps of natural salt from the shore. Even worse, they had to pay a heavy salt tax and were forced to buy salt from their British rulers. Gandhi felt deep injustice and started a preplanned chain of events to inuence his compatriots as well as the British rulers and to change the Salt Act as a step to the independence of India.

My ambition,” he wrote, “is no less than to convert the British people through nonviolence and thus make them see the wrong they have done to India.” The rst step was to write a letter to the Viceroy of India, Lord Irwin, in March 1930. Here are some excerpts from it.

“Dear Friend, Before embarking on Civil Disobedience and taking the risk I have dreaded to take all these years, I would fain approach you and nd a way out…Though I hold the British rule in India to be a curse, I do not therefore consider Englishmen in general to be worse than any other people on earth. I have the privilege of claiming many Englishmen as dearest friends. Indeed, much that I have learnt of the evil of British rule is due to the writings of frank and courageous Englishmen who have not hesitated to tell the unpalatable truth about that rule…For my ambition is no less than to convert the British people through non-violence and thus make them see the wrong they have done to India. I do not seek to harm your people. I want to serve them even as I want to serve my own…If people join me as I expect they will, the sufferings they will undergo, unless the British nation sooner retraces its steps, will be enough to melt the stoniest hearts…I respectfully invite you then to pave the way for an immediate removal of those evils and thus open a way for a real conference between equals. But if you cannot see your way to deal with these evils and my letter makes no appeal to your heart, on the 11th day of this month I shall proceed with such co-workers of the Ashram as I can take to disregard the provisions of Salt laws…It is, I know, open to you to frustrate my design by arresting me. I hope there will be tens of thousands ready in a disciplined manner to take up the work after me. I remain, Your Sincere friend. M.K. GANDHI”

The letter was widely publicized and Gandhi’s need to negotiate before taking drastic actions was obvious, but the reaction of the British Court was well described by Winston Churchill’s comment. One can picture the scene as the uniformed Viceroy sipped tea with the “half-naked fakir”. Viceroy Irwin turned down the interview and the Court laughed. On March 12, 1930. Gandhi and 78 men and women began their 241 miles long march from the ashram to the coastal town of Dandi. For 24 days they walked through village after village explaining their goal and by the time they reached Dandi on April 5, Gandhi was at the head of a crowd of tens of thousands. Gandhi picked up a small lump of natural salt out of the mud “With this,” he announced, “I am shaking the foundations of the British Empire.” Thousands of journalists and supporters gathered to watch him commit his symbolic crime. Some 80.000 people were arrested including Gandhi who was taken into custody. Others went on. Over 2500 marchers ignored warnings by police and made an unarmed advance on the salt depot. Journalist Webb Miller writes “Police rushed upon the marchers…and rained blows on their heads… Not one of the marchers even raised an arm to fend off the blows. They went down like ten-pins”. Winston Churchill admitted that protestors had “inicted such humiliation and deance as has not been known since the British rst trod the soil of India”. The world was astonished. Once the process started it could not be stopped and India gained its independence in 1947. Britain granted independence but split the country into two dominions: India and Pakistan. Gandhi urged Hindus and Muslims to live peacefully together – only months before Gandhi was shot dead by the militant Hindu named Nathuram Godse. Gandhi was adored and followed by millions of people during and after his lifetime but was also attacked by a few who objected his practice of sleeping with naked young ladies in the same room. His answer was that this behavior was practice of self-restraint behavior and self-control.

LESSONS LEARNED

- Gandhi was able to inuence Indians and Britons mostly through a referent power source. Most Indians loved and respected him while most Britons, even if they were no fans of Gandhi, had to respect him. Educated in London, he understood the Western need for justice and living in India he demonstrated empathy with oppressed Indians. He predicted the British arrest but also that Indians will continue after his arrest.

- Gandhi showed humility, a servant attitude and respect, while demonstrating against injustice towards Indians. No trace of hate, no prejudice, no belittling of British people.

- He literary “Walked the talk” and has set a personal example. His internal conviction, joy and respect for all parties including the British administration and the British sense for fair-play was exemplary.

- Gandhi has developed a visionary and strategic leadership plan together with tactical and operational elements around the “Salt law’’ despite doubts expressed by his colleagues. “We were bewildered and could not t in a national struggle with common salt” remembered Jawaharlal Nehru who later became India’s rst prime minister. Rather than launching a frontal assault on more high-prole injustices, Gandhi proposed to frame his protest around the visible and salient but common salt issue that was later branded as a world topic.

- While Gandhi demonstrated excellence in understanding British-Indian relationships and was superb in predicting their behavior he was much less capable in understanding and predicting the ethnic relationship between the Hindu and Muslim population in general and national extremists. The price to pay for this imperfection was his assassination. A leader can be superb in one situation but not so good in another. Therefore, one can be a leader and a follower depending on the situation.

- Gandhi’s action during the Salt march demonstrates risk proneness as a leadership quality and high standard in setting prominent values to follow: “I cannot intentionally hurt anything that lives” – he wrote to the Viceroy.

- One does not have to be perfect to become an effective leader in at least one area nor must one be perceived as faultless by everyone. Yet it seems there must be no cognitive dissonance within his/her value and ethics system as perceived by them.

Join our free Joyful Leadership online course today! Start here.

SOURCES:

- Joyful Leadership Manual